Shoreline Change Overtime Along the Coasts of Wolf Island and Egg Island

Jessie C. Moore Torres

Wolf Island is a Holocene island located along the Georgia coast on the mouth of the Altamaha River, between Sapelo and Little St. Simons Islands (31°21’00.47” N and 81°18’05.14” W). Wolf, Egg, and Little Egg Islands were all established as a collective U.S. National Wildlife Refuge on April 3, 1930 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). The Nature Conservancy originally owned the other 1,647 hectares of the island since 1969 until the rest was bought by the U.S. federal government on October 3, 1972. On January 3, 1975, it was designated as the Wolf Island National Wildlife Refuge, while also falling under the authority of McIntosh County, Georgia. The refuge is also designated as a migratory bird sanctuary and a sea-turtle nesting site. It is about 1,829 hectares in area, but the three-island refuge encompasses a total of 2,074 hectares, composed mostly of salt marshes. The eastern beach shoreline of Wolf Island is 6.4 km long, consisting of 121 hectares of dunes and beach sand; the beach-dune system is narrower than oceanfront beaches on other Georgia barrier islands (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). According to federal agencies and researchers who have studied the island refuge, the island’s environmental history has changed greatly through direct and indirect human presence.

During the 18th century, Wolf Island was used by American locals for hunting. Originally, 61 hectares of this island belonged to Christopher DeBrake, but were not granted to him by King George III of England until March 7, 1769 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). The island also served as a quarantine area for sailors infected by yellow fever (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). Then, in 1828, 218 hectares of Wolf Island were purchased by the U.S. government (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). The island also had lighthouses built on it during the 19th century, none of which exist today. However, the island’s location was useful for navigation, so the U.S. Coast Guard used it for a lighthouse, which presumably collapsed and sank (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). Similar to some of the other Georgia barrier islands, Wolf Island was also used actively during the American Civil War (1861-1865). This use occurred after construction of a second lighthouse on the island in 1822, which complemented the lighthouse on Sapelo Island, north of Wolf Island and across Doboy Sound. Despite this new ness, Confederate soldiers destroyed it during the Civil War to prevent the Union from using it for their navigation (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). A third (and larger) lighthouse with better light was built after the Civil War. However, it was destroyed by the 1898 Georgia hurricane, which also killed the lighthouse keepers. The Sapelo Island lighthouse then reused some of the remains of the Wolf Island lighthouse. A clubhouse on the southern end of Wolf Island was also destroyed (Lenz, 1999).

Although Wolf Island National Wildlife Refuge is a three-island system, Little Egg Island and Egg Island have different habitats compared to Wolf Island. Only 6.6% of Wolf Island consists of upland areas, and its highest elevation is 3.2 m (above mean low water), located on one of its several spoil sites; such areas contain soil or other sediments from activities such as excavations. The rest of the island is composed of salt marshes, small marsh hammocks, and tidal creeks. Egg Island has a relatively greater percentage of upland area (33.7%) and parts of the island are above 2.5 m; the rest of the island is dominated by salt marshes. Little Egg Island, however, lacks upland areas, as the entire island a low salt marsh.

Wildlife on Wolf Island also faces several threats, especially predation. For example, loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) nests are threatened by egg predators, such as Atlantic ghost crabs (Ocypode quadrata), raccoons (Procyon lotor), and feral hogs (Sus scrofa) (National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1991). Ghost crabs tend to locate the sea turtle nests, burrow to the nest cavity to obtain the eggs, and bring them up to the surface for consumption (Marco et al., 2015). During sea-turtle nesting season, raccoons wander through beaches and consume sea turtle eggs. They dig into nests until they locate an egg mass (Bishop et al., 2009). Finally, feral hogs, an invasive species, are infamous for destroying 100% of any given sea turtle nests by rooting them into cone-shaped depressions (Bishop et al., 2009). Because raccoons and ghost crabs are native to the island, reducing their populations would be difficult and would have significant ecological effects. However, feral hog populations should be reduced and/or eliminated from the island to best avoid sea turtle nest destruction.

Sea-turtle nesting is an issue on Wolf Island, but not as much as on most other Georgia barrier islands. Wolf Island averages only five sea turtle nests per year (U.S. Department of the Interior. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008); some of these are destroyed by tidal inundation as well as by native and nonnative fauna. Tidal inundations are also more likely on Wolf Island owing to its lack of primary dunes. Its lack of dunes must considered when studying the small number of sea turtle nests on Wolf Island, especially because loggerhead sea turtles reproduce by laying eggs in subsurface nests. These nests are excavated in the backbeach or sand dunes behind beaches, which allows the eggs to incubate and hatch (Bishop et al., 2009). However, few turtle conservation efforts are done on Wolf Island because of its low number of sea turtle nests (U.S. Department of the Interior. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). Little Egg Island (31.3155° N and 81.2993° W), which is about 6 hectares in area, is recognized for its colony of royal terns (Thalasseus maximus), the only place they are known to nest in Georgia. However, some studies show royal tern populations dramatically increased and decreased over time during the 1950’s, and then the 1960’s (Kale, 1965). Because royal terns tend to nest in areas covered with vegetation, their decrease has been attributed to destruction of nesting habitat by high tides. Relict marsh and sandy areas cover Little Egg Island more than areas with vegetation. Therefore, these colonies will likely continue to diminish with future increases in sea level rise.

Other aspects of Wolf Island, such as the climate and vegetation, share similarities with other Georgia barrier islands. The island has an average annual precipitation of 141 cm (National Weather Service, 2017). It receives low mesotidal energy from semidiurnal tides, averaging approximately 2-3 m in height (Bishop, 2009). In the upland portions of Wolf Island, are sea oats (Uniola paniculata), sand spurs (Cenchrus tribuloides), and wax myrtles (Myrica cerifera). Salt marshes composed of smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) and sea ox-eye (Borrichia frutescens) surrounding higher elevations and beach areas. Plants on the beach include sea rocket (Cakile spp.), beach hogwort (Croton punctatus), salt meadow cordgrass (Spartina patens), salt wort (Salsola kali), sea-purslane (Sesuvium spp.), beach-spurge (Euphorbia polygonifolia), and seahorse-elder (Iva imbricate) (U.S. Department of the Interior. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). Egg Island (31°18′17″N and 81°18′05″W) is mostly composed of marsh and forested areas of about 240 hectares in area. Sandy beaches are on the southeastern area of the island, but these are not ecologically significant as marsh, tidal creeks, and forest. For example, some oak and pine trees in the forested areas are used by migratory birds. Egg Island Bar (31°18’32.31” N and 81°16’45.02” W), located northeast to Egg Island, supports a large colony of royal terns, with more than 9,000 pairs (Lenz, 1999), in addition to a colony that used to be on Little Egg Island. It is also used as a nesting ground for black skimmers (Rynchops niger), gull-billed terns (Gelochelidon nilotica), and brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis). Because Egg Island is closed to the public, not much research has been done on it. Specifically, this paper only focuses on Wolf and Egg Islands because the data that was collected for the three-island system of Wolf Island National Wildlife Refuge does not properly display Little Egg Island for some years.

Research

Based on this information, island area calculations and a shoreline analysis were conducted for Wolf and Eggs Islands. This project was conducted during the Fall of 2017 and was titled “Shifting Shorelines on Wolf and Egg Islands, Georgia, USA: A Study of Change Since 1953.”

Island area was calculated for Egg Island in the years 1953, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1982, 2009, and 2015 with a polygon shoreline (Figure 1). Aerial photographs and NAIP images of Egg Island were georeferenced before they were digitized along shoreline (Table 1). The polygons cover the entire island instead of using a single line along the high-water mark (Fearnley et al, 2009). The total area of Egg Island was measured in square meters and was plotted against the years that were analyzed for this specific island (Figure 3).

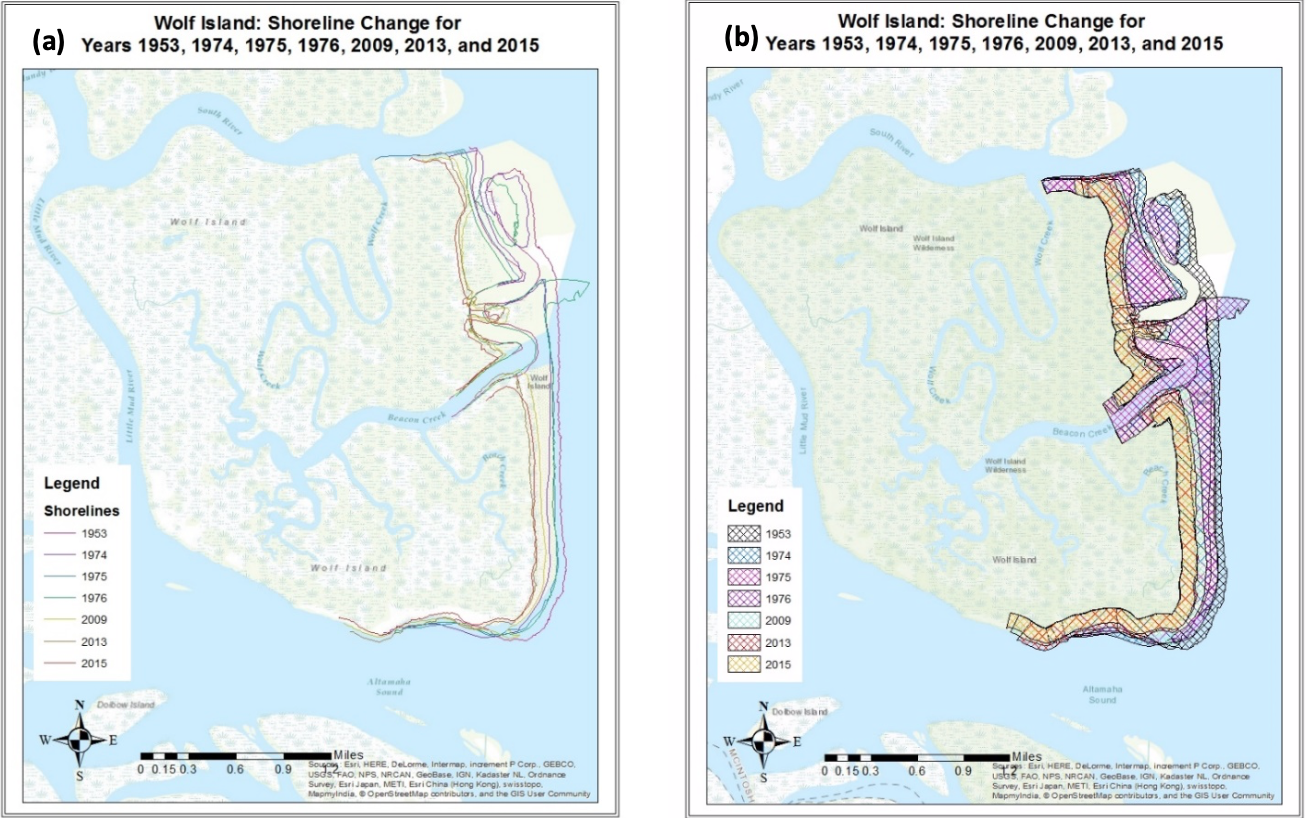

With data from Table 2, shoreline change analysis was used by creating linear measurements along the east coast of Wolf Island (Figure 2a). An aerial photograph from 1976 did not have the frame that contained the northwest corner of Wolf Island. Because of this, the shoreline change analysis was done on the east coast of the island rather than having performed an island area calculation similar of that to what was done for Egg Island. Authors such as Dolan et al. (1991) have used other methods for calculating shoreline change, such as end point rate (EPR), average of rates (AOR), linear regression (LR), and jackknife (JK) methods. However, in this study, shoreline change was calculated using a baseline created from a buffered shoreline in ArcMap. Polygons were then made by connecting the baseline with the shoreline that was digitized for each year (Figure 2b). The area from the polygons were calculated in square meters in order to give the total area that was covered between the baseline and the shorelines. Similar to the island area calculation done on Egg Island, the total area of these polygons were also plotted against the years that were observed for Wolf Island (Figure 4).

When observing the results, three errors need to be considered. These can be errors in accuracy of shoreline measurements, uncertainties when georeferencing the photographs, mapping and digitizing in accordance to the quality of the photographs, and calculation errors for the total areas. This also includes GPS positioning errors and errors from the resolution of imagery (Fearnley et al, 2009)

Egg Island showed periods of erosion from 1974 to 1977 (Figure 3). The most recent measurements from 2015 show the accretion that is occurring in the southeastern region of the island, which is indicative of its location by the mouth of the Altamaha River. Table 3 shows the difference in area in between each year that was observed, where the next consecutive year was subtracted with its previous year. The negative values indicate erosion whereas positive values indicate accretion. The Altamaha River exits and initiates longshore drift from the northern part of the island to the southeastern part of the island. The accumulation of sediment on the southeastern part of Egg Island causes it’s change in shape over time. Wolf Island has had erosion since 1974 (Figure 4). According to the results from Table 4, Wolf Island continues to erode, more specifically in the northeastern tip of the island. This can be due to sea-level rise or longshore drift coming from north to south, parallel to Wolf Island’s shoreline. Additionally, because of this, one notices Wolf Island’s transgressive nature in relation to the Georgia coast.

Before Wolf Island became a National Wildlife Refuge, the island was more accessible to researchers. As a result, the island lacks the latest research. Hopefully, future researchers will also study the impacts of salt-water intrusion on current relict marshes and on infauna that used to live in environments specific to Wolf Island.

Works Cited

Bishop, G.A., Pirkle, F.L., Meyer, B.K., and Pirkle, W.A.. 2009. Chapter 13: The Foundation for Sea Turtle Geoarchaeology and Zooarchaeology: Morphology of Recent and Ancient Sea Turtle Nests, St. Catherine’s Island, Georgia, and Cretaceous Fox Hills Sandstone, Elbert County, Colorado. Anthropological Papers American Museum of Natural History 94: 247-69. American Museum of Natural History. Web. 7 Apr. 2017. https://digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/6105.

Clayton, T.D., and National Audubon Society.1992. Living with the Georgia Shore. Durham: Duke UP. Print.

Dolan, R., Fenster, M.S., and Holme, S.J. 1991. Temporal Analysis of Shoreline Recession and Accretion. Journal of Coastal Research 7: 723-744.

Fearnley, S., Miner, M., Kulp, M., Bohling, C., Martinez, L., and Penland, S.. 2009. Chapter A. Hurricane impact and recovery shoreline change analysis and historical island configuration—1700s to 2005, in Lavoie, D. (editor). Sand Resources, Regional Geology, and Coastal Processes of the Chandeleur Islands Coastal System—An Evaluation of the Breton National Wildlife Refuge: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2009-5252: 7-26.

Hoyt, J.H., Weimer, R.J., and Henry, V.J., Jr. 1964. Late Pleistocene and recent sedimentation on the central Georgia coast, U.S.A. In van Straaten, L.M.J.U. (editor), Deltaic and Shallow Marine Deposits, Developments in Sedimentology I. Elsevier, Amsterdam: 170-176.

Kale, H.W., Sciple, G.W., and Tomkins, I.R. 1965. The Royal Tern Colony of Little Egg Island, Georgia. Bird-Banding, 36 (1): 21-27., www.jstor.org/stable/4511131.

Kellam, J.A., Bonn, G.N., Laney, M.K., and Geological Survey.1992. Distribution of Heavy Mineral Sands Adjacent to the Altamaha Sound : An Exploration Model. Atlanta: Georgia Dept. of Natural Resources, Environmental Protection Division, Georgia Geologic Survey. Bulletin (Georgia Geologic Survey) ; 110. Print.

Lenz, R. J. 1999. Longstreet Highroad Guide to the Georgia Coast & Okefenokee. Atlanta, Ga.: Longstreet. 209. Print.

Marco, A., et al. 2015. “Patterns and Intensity of Ghost Crab Predation on the Nests of an Important Endangered Loggerhead Turtle Population.” Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, vol. 468, 14 Mar. 2015, pp. 74–82., ruifreitas.info/Marco_etal_Loggerheads_nests.

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for U.S. Population of Loggerhead Turtles. Washington, D.C.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA's National Weather Service. U.S. Dept. of Commerce. Accessed August 30, 2017. https://www.nws.noaa.gov/.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Wolf Island National Wildlife Refuge: Comprehensive Conservation Plan. By Shaw Davis. Atlanta: U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service. Print.